‘The Champion of Emblazon’

Today’s post is a look at one specific Jewish Armorial Insignia, and will hopefully be the first in a series. This story takes us back to the 14th century of the common era.

An armiger is someone who bears armorial bearings, by grant, registration or assumption. Some armigers are happy to create their arms and have them hanging somewhere in the house and so on.. Others feel the need to spread word of the arms they use far and wide. This can be done by multiple registrations nowadays. In the past, participating in jousting tournaments and doing other things to spread one’s reputation could bring renown to the arms and name. One Possible avenue for this would be to be an art patron, thereby having your arms sculpted or painted on your commissions.

In regards to Jewish heraldry, it is considered lucky to have the knowledge about arms survive from some time back in (even fairly recent) history to today. We do not encounter many Jewish armigers with more than one reference to their coat of arms. One such fascinating case is that of Daniel ben Samuel.

This medieval Jewish patron of the arts, was clearly a man of literature and books, a Rabbi or Dayan (Judge, possibly used the term as a surname), either he or his father were a Doctor (of medicine), and was a descendant of a prominent Jewish family in Italy of the 14th century, a very troubled period of Italian history. The era was that of the Ghibelline-Guelph ‘civil’ war and everyone was expected to take sides. Presumably, this was true for Jews too. So what do we know about Rabbi Daniel and his Ancestry?

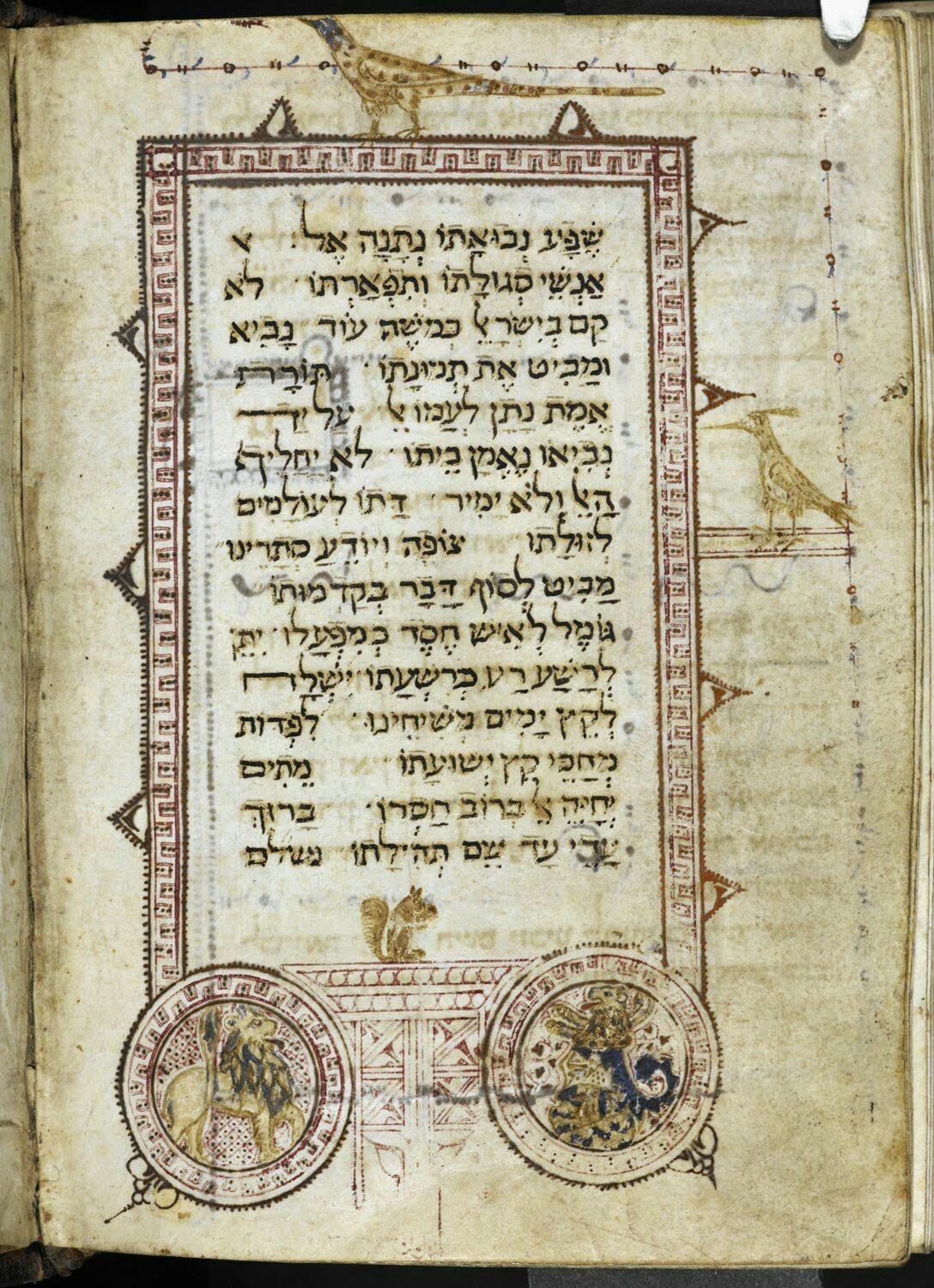

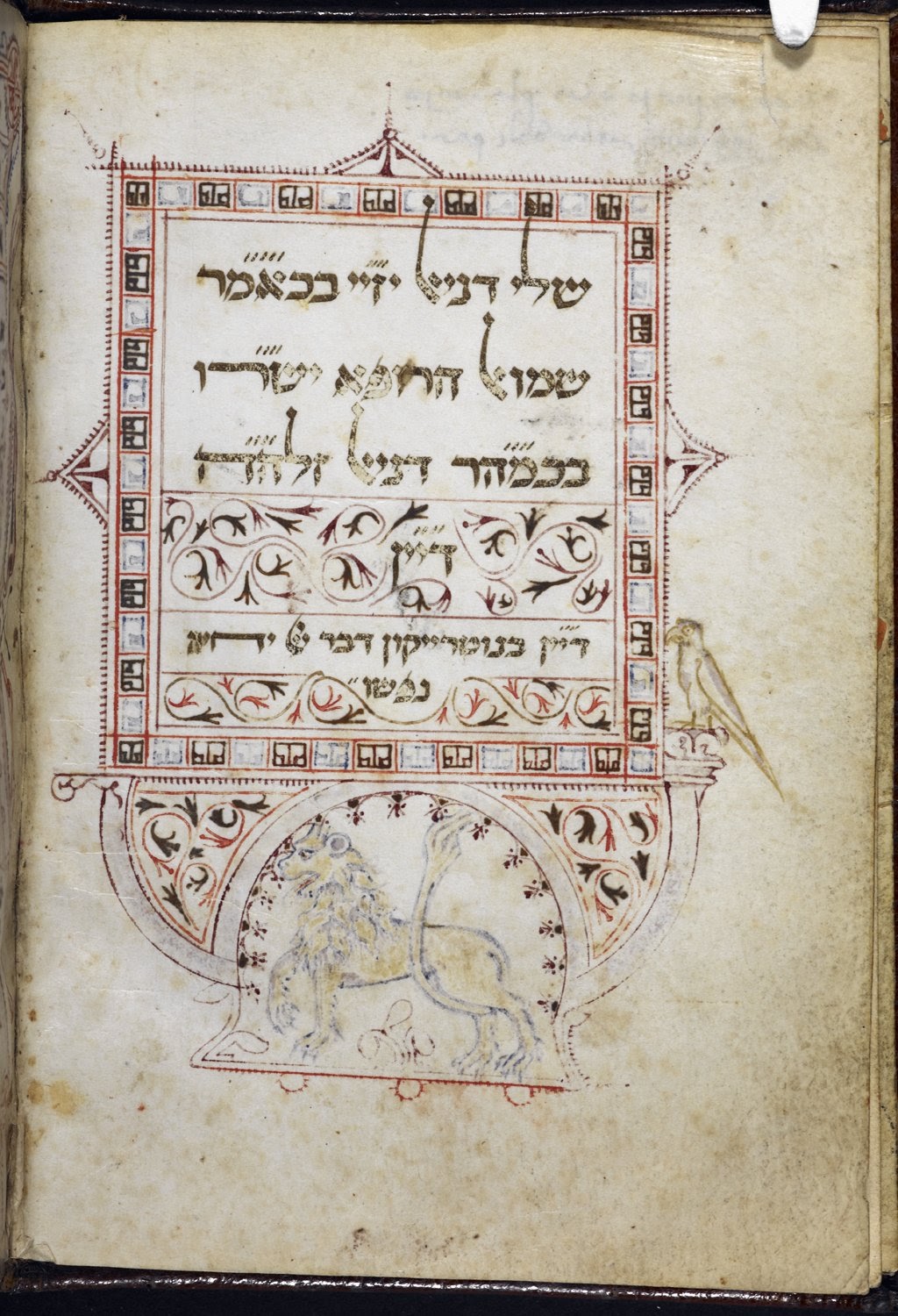

Four Manuscripts are to be found today that were commissioned by Rabbi Daniel, each illuminated to different degrees. The manuscripts were created between 1383-1396 In Forlì, Bartenura [Bertinoro] and Pescia (or Pisa). The first two locations are adjacent towns in northern Italy, south of the mouth of the Po river and near the Adriatic sea. Pescia is not far from Pisa, both are on the other side of the Apennine mountain range that crosses Italy, on the same latitude as the previous two. So all were created within a rather small geographical area. Two manuscripts are in the British library today, one in the Bodleian library, Oxford. A fourth is in the Jewish museum of Venice and doesn’t seem available online.

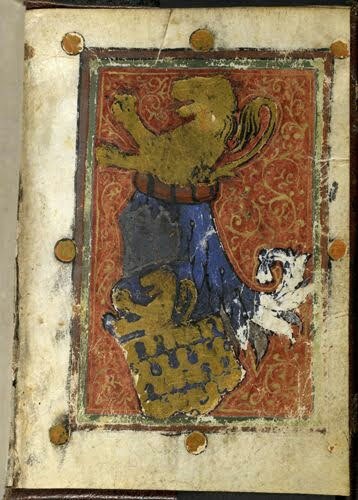

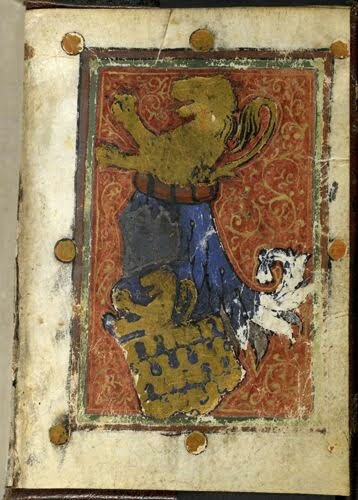

A repeating theme – All (certainly the three available online) carry Armorial Bearings, rather clearly regarded as Rabbi Daniel’s arms, by the presence of his name and titles underneath or on the same page as the arms, in several instances. These are no simple crude shields either. Some are very elaborate indeed, both in design and in artistic execution. They include not only Shield, but also helm, crest, mantling and wreath (a kind of Sudarium in Mishnaic terms, or in Arabic a Keffiyeh/Ghutrah & Iqal painted between Helm & Crest). A helmet and crest being quite rare in Italian heraldry, even for actual warring Knights. Some of these images are found in this post. All counted, eight drawings of the arms of Rabbi Daniel appear in these manuscripts, four in the Forli Siddur, prayer book or order of services (1383), three in the Bertinoro Siddur (1390) and one, though the most impressive, in the Rashi commentary on the Pentateuch (1396) probably made in Pisa.

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, the grandfather of Daniel, also a Daniel, wrote the liturgical hymn or poem – Yigdal Elokim Chai (יגדל אלקים חי – Exalted be the Living G-d) which seems to have received wide circulation even back then, and indeed to this day serves as a basic part of the morning prayer service according to many of the regional customs. The intermediate generation, Rabbi Samuel, was rabbi of Tivoli In central Italy, and so it would appear that the family moved northward from Rome to the Emilia-Romagna region. As we can clearly tell that the grandson R’ Daniel was quite affluent, since he could afford such luxuries as commissioning four separate illuminated manuscripts in a matter of several years, this movement north was probably motivated by a successful business of some sort. Which brings us back to the matter of the apparent family insignia. Why this design? What did it mean?

This is a question that normally is entirely too difficult to answer, especially for arms of the early centuries of European heraldry, since there are little to no written sources about the various arms, just their actual pictorial representations. But Jewish heraldry has some helpful elements in this matter. As the jews were in exile and were treated as such by the Christian communities where they resided (forming a separate legal community) – they required patrons, protectors, that represented them legally and had a symbiotic relationship with. These were usually the kings or high nobles of the area. Therefore, the Jews had in many cases a sort of right or claim thereof, for use of the arms of these patrons or a cadency (close derivative) of such arms, this being one element helping identification. This is most probably the reason for the appearance of such royal arms in many Jewish illuminated manuscripts, a sort of show of fidelity – yes, but one that placed a claim to the arms or a connection to them on behalf of the commissioner of the work.

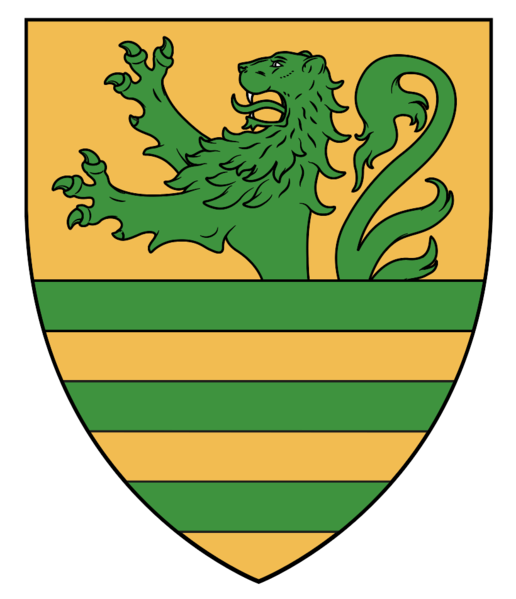

It so happens, the Lords of Forli at the turn of the 14th century, of the house of Ordelaffi, were using arms quite similar, though different, to those shown on these works for R’ Daniel ben Samuel. The arms of the Lords of Forli were: Per fess Or a Lion issuant Vert and Barry of six all counterchanged. The arms presented for R’ Daniel were: Per fess Azure a Lion issuant Or and Barry wavy (nebuly?) of six all counterchanged. In layman’s terms – both arms consist of a shield divided by a horizontal line, the top half featuring half the figure of a lion emanating from the dividing line, and the bottom half divided further into six lines. So the differences were the use of Azure (blue) by R’ Daniel instead of the local lord’s Vert (green), changing the color order (tincture/metal) in the upper part and the lines being wavy in his arms.

If this hypothesis is correct, then this is a rather classic case of differencing arms with two alterations for cadency (actually three in this case). That is, using similar arms, for show of patronal or even feudal relationship. Perhaps the fortune of R’ Daniel was made serving the lords of Forli in some way, like collecting taxes on their behalf, operating a usury business licensed by them or something similar. That would fit well within a known customary relationship in the medieval period, between wealthy members of the Italian Jewish communities and local rulers. Forli was the host in 1418, several years after the production of these works, of an assembly of Rabbis from across the region. The decisions from this convention are known as the Takanot Italia (regulations of Italy), were regarded for several decades at least as binding and form an important part of history for Italian Jewry. This seems to show a favorable atmosphere for Jews by the ruling Ordelaffi lords.

Sources & Links:

- Wikipedia: Daniel ben Judah ; Yigdal ; Forli ; House of Ordelaffi.

- Wappenwiki: House of Ordelaffi

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Daniel ben Judah

- British Library: Siddur Forli ; Siddur Bertinoro.

- Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: Commentary on Pentateuch

- Louis Finkelstein, Jewish Self-Government in the Middle Ages, Feldheim publishers, 1964, USA. (Part I, Takkanot of Italy, pp. 86-96. Part II, Takkanot, pp. 281-316.)